“Consuming raw seafood may increase your risk of death.”

“Evil witch advisory.”

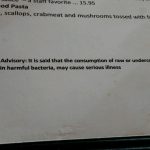

Yes, these are actual advisories I’ve seen on walls and restaurant menus. I’m sure someone considered them funny. But there is nothing funny about a foodborne illness.

Perhaps these “off the wall” methods did get more people’s attention than the more traditional advisory statement: Consuming raw or undercooked meats, poultry, seafood, shellfish or eggs may increase your risk of foodborne illness, especially if you have certain medical conditions.

What’s a consumer advisory? They are warnings required when a restaurant serves a food product that could possibly cause a foodborne illness. This includes animal foods such as beef, eggs, fish, lamb, milk, pork, poultry or shellfish that are served raw or undercooked. The concept is that an educated consumer can make their own decision on whether to eat these foods or not.

The foods listed on advisories are possibly harmful when served raw or undercooked are known in the industry as potentially hazardous foods—these are foods that have caused illnesses in the past. Typically most of the bacteria are destroyed by cooking, but when the food is served raw or undercooked, an illness may occur if the bacteria count is too high.

If you’ve seen these advisories, are you paying attention to them? It could mean YOU.

Of course not everyone who eats these foods will get sick. Certain groups of people have a higher risk than others. These include the elderly, preschool age children, and those who have a compromised immune system such as people with cancer or those who are on chemotherapy, people with HIV/AIDS, and transplant recipients. Others at risk are those with liver disease and alcoholism and people taking certain medications. If you have concerns that you may be included in this list, check with your health professional.

People’s immune systems weaken with age or disease and it’s this immune system that serves as the body’s defense against illness—including foodborne illnesses. You may have been able to eat some foods undercooked or raw in the past, but need to use more caution as you get older.

Very young children have not yet built up strong immune systems. Because of this, children’s menus should not include raw or undercooked meat, poultry, seafood, or eggs. One item children should especially avoid is undercooked ground beef.

The cavalier attitude of these restaurants regarding the advisories makes me wonder what’s the attitude in the kitchen. The great sanitarians in my county said that these consumer advisories would not be acceptable to them and the restaurants would lose points on their inspection scores. While some restaurants and chefs may take these advisories lightly….people at-risk shouldn’t.

The cavalier attitude of these restaurants regarding the advisories makes me wonder what’s the attitude in the kitchen. The great sanitarians in my county said that these consumer advisories would not be acceptable to them and the restaurants would lose points on their inspection scores. While some restaurants and chefs may take these advisories lightly….people at-risk shouldn’t.

Cheryle Jones Syracuse, MS

Professor Emeritus, The Ohio State University

I like to ask sanitarians and other food safety experts what foods they WON’T eat. One item that’s always on their list is raw sprouts.

I like to ask sanitarians and other food safety experts what foods they WON’T eat. One item that’s always on their list is raw sprouts. A similar food, that’s becoming popular are microgreens. They are “cousins” to sprouts but less risky. Sprouts are consumed entirely– leaves, stem, roots and possibly seeds, while only the stems and leaves of microgreens are eaten (similar to fresh herbs). One big difference is that you don’t consume the seed portion of a microgreen—seeds tend to be one of the sources of contamination in sprouts. Another difference is that microgreens are grown in dirt not just water like sprouts.

A similar food, that’s becoming popular are microgreens. They are “cousins” to sprouts but less risky. Sprouts are consumed entirely– leaves, stem, roots and possibly seeds, while only the stems and leaves of microgreens are eaten (similar to fresh herbs). One big difference is that you don’t consume the seed portion of a microgreen—seeds tend to be one of the sources of contamination in sprouts. Another difference is that microgreens are grown in dirt not just water like sprouts.